by Michael Mejia | Mar 29, 2022 | Moot Court Mondays

3M corporation, long a staple of American industry, has recently been rocked by a string of lawsuits related to defective earplugs it sold to the U.S. military in what has been termed the largest multi-district litigation in U.S. history.1 As of the writing of this article, plaintiffs (all former U.S. military veterans have been awarded a staggering combined amount of $160 million in six bellwether trials.2 The entire controversy stems from 3M’s 2008 acquisition of Aearo Technologies, the company which manufactured the earplugs.3 The reason Aearo’s design of earplugs appealed to the U.S. military resulted from its innovative design: the dual-ended design allowed one end to block out as much sound as possible while the other end protected a user’s ears from extremely loud noises such as gunfire or explosions.4 This design was advantageous because it allowed troops to communicate with fellow soldiers nearby during loud situations.5

3M corporation, long a staple of American industry, has recently been rocked by a string of lawsuits related to defective earplugs it sold to the U.S. military in what has been termed the largest multi-district litigation in U.S. history.1 As of the writing of this article, plaintiffs (all former U.S. military veterans have been awarded a staggering combined amount of $160 million in six bellwether trials.2 The entire controversy stems from 3M’s 2008 acquisition of Aearo Technologies, the company which manufactured the earplugs.3 The reason Aearo’s design of earplugs appealed to the U.S. military resulted from its innovative design: the dual-ended design allowed one end to block out as much sound as possible while the other end protected a user’s ears from extremely loud noises such as gunfire or explosions.4 This design was advantageous because it allowed troops to communicate with fellow soldiers nearby during loud situations.5

In a recent filing, 3M sought to appeal its first trial loss in the massive multi-district litigation. In its appeal before the Eleventh Circuit, the company’s lawyers sought to invoke a legal doctrine known as the government-contractor defense.6 Essentially, the company argued that this federal doctrine preempted the plaintiff’s state law claims of product defect and failure to warn.7 The defense has its roots in the concept of sovereign immunity.8 The essential elements for this defense were resolved in the case of Boyle v. United Technologies Corp. pursuant to a split among the circuits.9 Based upon the rule articulated in Boyle, 3M would have to prove the following elements in order to avoid liability: (1) the United States approved reasonably precise specifications [of the product’s design]; (2) the equipment conformed to those specifications; and (3) the supplier (3M) warned the United States about the dangers in the use of the equipment that were known to the supplier but not to the United States. 10 Invocation of this defense may signal a strategic shift in how 3M handles the flurry of litigation that has arisen from this tragic issue. Either way, this recent filing could set the stage for the mountain of other cases the embattled conglomerate is confronted with.

1 Brooke Sutherland, 3M Adds Another Legal Worry to Its Pile of Headaches, BLOOMBERG, Feb. 14, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-02-14/3m-adds-an-earplug-legal-worry-to-its-pile-of-headaches. 2 Nate Raymond, 3M on appeal says first trial in massive earplug litigation went ‘off the rails,’ REUTERS, Feb. 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/3m-appeal-says-first-trial-massive-earplug-litigation-went-off-rails- 2022-02-25/.

3 Supra note 1.

4 Id.

5 Id.

6 Id.

7 Id.

8 Steven Brian Loy, NOTE: The Government Contractor Defense: Is It a Weapon Only for the Military?, 83 Ky. L.J. 505, 506.

9 Id.

10 Id.

by Daysi Vega-Mendez | Mar 29, 2022 | Moot Court Mondays

The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) of 2000, provides that no substantial burden can be imposes on the religious exercise of a person, including state prisoners, unless the imposed burden is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest. However, RLUIPA only protects a prisoner’s requested accommodation when it is sincerely based on a religious belief and not some other motivation.

The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) of 2000, provides that no substantial burden can be imposes on the religious exercise of a person, including state prisoners, unless the imposed burden is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest. However, RLUIPA only protects a prisoner’s requested accommodation when it is sincerely based on a religious belief and not some other motivation.

In a recent Supreme Court decision, Ramirez v. Collier Executive Director, Texas Department of Criminal Justice, et al., the court determined whether Ramirez’s execution should be halted until his requests for his execution were considered. Ramirez wanted his pastor to come inside the execution room with him, lay hands on him, and pray over him. The Court considered similar cases in 2020 and 2021, holding that executions could not proceed unless the inmates’ spiritual advisors were allowed to be present. The Ramiez case differs in that Ramirez requested his pastor’s physical touch.

Texas claimed two compelling interests in denying Ramirez’s request for his pastor to pray with him: (1) that absolute silence was necessary in order for proper monitoring of the inmate’s condition and (2) that the spiritual advisor could choose to make a statement to the witnesses or the personnel in the execution room, instead of to the inmate. Although the justices recognized that these interests were compelling, the majority was not persuaded that the state’s policy was the least restrictive means of protecting these interests. The court went through the long history of having audible prayer at a prisoner’s execution, making note of the fact that religious advisors were allowed to speak or pray audibly during at least six federal executions between 2020-2021. The court further recognized some lesser restrictions on audible prayer that could be adopted in furtherance of the state’s claimed interests, such as limiting the volume of prayer or requiring silence during certain moments of the process.

The state asserted three interests in banning religious touch in the execution chamber: (1) the spiritual advisor would be placed in harm’s way in the event that the inmate escapes or biomes violent, (2) the spiritual advisor might interfere with an IV line and cause more suffering to the inmate in their final moments, and (3) the victim’s family would be traumatized because their loved one did not receive the same. Again, the Court acknowledged the validity of maintaining safety and decorum in the chamber as a compelling governmental interest. But, the Court made notice of Texas’s policy of allowing spiritual advisors to be three feet from the gurney and failed to see how allowing the advisor to simply reach out their hand to touch the inmate would increase any risk of danger.

Because the state failed to meet its burden, the Court determined that it was likely that Ramirez would succeed in an RLUIPA claim and remanded the case.

Links

by Liz Guinan | Mar 7, 2022 | Moot Court Mondays

Android, built on Java software code, provides power to a majority of the mobile devices in the world. Android was developed and run by technology super house Google. Google states that they used elements of this Java code for operations. This methodology, originally spun by the technology giant Oracle, led to a public feud in 2011. Oracle claimed Google had copyrighted exact lines of a Java code they had created to complete their technology development. Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021).

Android, built on Java software code, provides power to a majority of the mobile devices in the world. Android was developed and run by technology super house Google. Google states that they used elements of this Java code for operations. This methodology, originally spun by the technology giant Oracle, led to a public feud in 2011. Oracle claimed Google had copyrighted exact lines of a Java code they had created to complete their technology development. Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021).

The case is marked by several flip-flopping verdicts and has left some loose ends. Judge Alsup in 2012 gave a ruling that APIs are not subject to copyright law. In 2014, the Federal Circuit reversed that decision and put forth a new ruling that Java code is copyrightable. However, the floor was open for Google to present a defense. Google appealed in 2018 with Oracle, initially seeking close to ten billion dollars in damages. That number soon renewed to closer to $30 billion. Oracle’s suit claims that Google copied lines of Java programming code and used that code directly from Android. Oracle and Google’s main areas of dispute were surrounding fair use. The Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments in 2020.

They reviewed the documents and verdicts presented that led to the decisions passed down by the U.S. Court of Appeals for The Federal Circuit. The Court went over four key aspects to determine whether or not the copying of API was fair use. These aspects could be found in the Copyright Act’s fair use section. These guiding factors on fair use included the purpose of the use, the nature of the work, the effect on the market, and the amount of the portion used. After over a decade of dispute, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Google, deciding that the technology giant did not commit copyright infringement when developing Android. In this 6-2 vote with Justice Breyer preceding, the case was considered an example of fair use.

Justices were concerned that a ruling in favor of Oracle could lead to monopolization. When in discussion, the Justices expressed that they understood the more profound importance of Software creation and the capabilities of Java. “There are a thousand ways of organizing things, which the first person who developed them, you’re saying, could have a copyright and prevent anybody else from using them,” Chief Justice Roberts had stated. Software creators that have developed technology will not be able to hold a monopoly over the technology, meaning that it will be available for use by other companies, programmers, and developers.

The Supreme Court ruling in favor of Google, Inc. on the primary means of creative technological freedom could open new doors for other companies to do the same. The technology industry has supported the decision, noting that it now allows companies and developers to extend the fair use of computer code. Developers who wish to have more creative liberty without facing legal repercussions may have more creative freedom that will benefit consumers.

Sources:

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/18-956

https://www.westlaw.com/Document/Id3df6529961311ebbb10beece37c6119/View/FullText.html?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&VR=3.0&RS=cblt1.0

https://www.project-disco.org/intellectual-property/100820-justices-display-concern-about-monopolization-disruption-in-google-v-oracle-oral-argument/

by Ricardo Jerome | Mar 1, 2022 | Moot Court Mondays

The Establishment Clause is a clause that comes from the First Amendment of the United States. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”.[1]

The Establishment Clause is a clause that comes from the First Amendment of the United States. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”.[1]

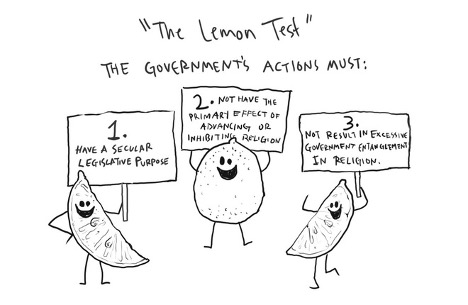

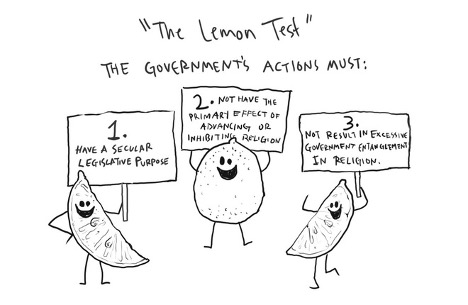

In a recent Supreme Court decision, Town of Greece v. Galloway, it highlights the struggle between the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause, which embodies the issues most justices have struggled to come to terms with: whether the law is promoting a religious affiliation, whether the law is infringing on religious beliefs, and where to draw the line when deciding how Establishment Clause violations should be tested. The central question in the case was whether a town in New York called Greece, was in violation of the Establishment clause by allowing town meetings to hold prayers which respondents claimed to favor the Christian religion. There was never any reviews of the prayers that were given in these town meetings due to the belief that trying to exercise any control of these prayers would violate the free exercise and free speech rights that the minister had as they would give these prayers.[2] Eventually, there were several citizens who filed a suit against these prayers claiming the Establishment Clause was being violated because they felt that the Christian faith was being favored over other faiths in the prayers.[3] In Town of Greece v. Galloway, the court ruled that these prayers which were invocated in the meetings were not unconstitutional and relied on the fact that these so called legislative prayers were ongoing and uninterrupted for years before there was any claim against them. Town of Greece v. Galloway in essence relied on a historical analysis to determine that the Establishment Clause was not being violated by the town. This is not truly a standard held by the Lemon Test which is the widely held Establishment Clause test. It is a three-prong test meant to prove that law or legislation violates the Establishment clause if it does not have a secular legislative purpose, if its primary effect advances or inhibits religion, and if it fosters excessive government entanglement with religion. Town of Greece v. Galloway begs the question of whether a historical use of specific religious practices in certain areas should be analyzed while applying the Lemon Test as an aid to determine whether there has been a violation.

[1] See U.S. CONST. amend. I.

[2] See Town of Greece, N.Y. v. Galloway, 572 U.S. 565, 571 (2014).

[3] See Town of Greece, N.Y, 572 U.S. at 565 (stating “respondents, citizens who attend meetings to speak on local issues, filed suit, alleging that the town violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause by preferring Christians over other prayer givers and by sponsoring sectarian prayers.”).

Links:

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/first_amendment

- https://plus.lexis.com/document/?pdmfid=1530671&crid=595b8826-d727-44cf-8107-02a0f5e2472c&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fcases%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A58FW-XXV1-F04K-F00J-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=6443&pdteaserkey=&pdislpamode=false&pdworkfolderlocatorid=NOT_SAVED_IN_WORKFOLDER&ecomp=ff4k&earg=sr10&prid=ca586865-251e-4e92-b03e-218de6eeb15d

by Emily Chahede | Feb 21, 2022 | Moot Court Mondays

Covid has brought about many changes in the United States legal system, specifically in the context of incarceration. In this recent opinion the Defendant, Mr. Jones (“Mr. Jones”), was convicted pursuant to Criminal Punishment Code Scoresheet, Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 9.992. The lowest sentencing that was provided to Mr. Jones was twenty-one months in state prison. Due to the onset of COVID the sentencing was delayed, and Mr. Jones sought an alternative sentencing of two years in community control followed by a three-year probation. Ms. Jones was ultimately asking the Court to allow for a longer sentencing outside of prison to prevent contracting COVID-19. At the time of his sentencing the current statistics provided that over 31,000 Floridians had tested positive for COVID-19 including over 1,000 deaths. Mr. Jones was also fifty years old at the time of his sentencing and the sole medical issue he pointed to be the testimony of father that claimed he had high blood pressure. However, the basis of the argument was not on the medical condition itself, but on the global pandemic.

Covid has brought about many changes in the United States legal system, specifically in the context of incarceration. In this recent opinion the Defendant, Mr. Jones (“Mr. Jones”), was convicted pursuant to Criminal Punishment Code Scoresheet, Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 9.992. The lowest sentencing that was provided to Mr. Jones was twenty-one months in state prison. Due to the onset of COVID the sentencing was delayed, and Mr. Jones sought an alternative sentencing of two years in community control followed by a three-year probation. Ms. Jones was ultimately asking the Court to allow for a longer sentencing outside of prison to prevent contracting COVID-19. At the time of his sentencing the current statistics provided that over 31,000 Floridians had tested positive for COVID-19 including over 1,000 deaths. Mr. Jones was also fifty years old at the time of his sentencing and the sole medical issue he pointed to be the testimony of father that claimed he had high blood pressure. However, the basis of the argument was not on the medical condition itself, but on the global pandemic.

On appeal, the court analyzed Section 921.0026, Florida Statutes (2013), which considers “Mitigating Circumstances” to Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code. The statute provides a non-exhaustive list for circumstances that allow the downward departure of a sentencing. To support a claim under this statute the defendant must provide competent substantial evidence to succeed on the stated basis. See State v. Hodges, 151 So. 3d 531 (Fla. 3d DCA 2014); State v. Bowman, 123 So. 3d 107 (Fla. 1st DCA 2013).

As noted by the Florida Supreme Court, the analysis a court must take is a two-part test:

“First, the court must determine whether it can depart, i.e., whether there is a valid legal ground and adequate factual support for that ground in the case pending before it (step 1). . . . This aspect of the court’s decision to depart is a mixed question of law and fact and will be sustained on review if the court applied the right rule of law and if competent substantial evidence supports its ruling.

Second, where the step 1 requirements are met, the trial court further must determine whether it should depart, i.e., whether departure is indeed the best sentencing option for the defendant in the pending case. In making this determination (step 2), the court must weigh the totality of the circumstances in the case, including aggravating and mitigating factors. This second aspect of the decision to depart is a judgment call within the sound discretion of the court and will be sustained on review absent an abuse of discretion.”

Banks v. State, 732 So. 2d 1065 (Fla. 1999).

Following jurisprudence established by the Second District Court of Appeal, in State v. Saunders, 322 So. 3d 763, 767 (Fla. 2d DCA 2021). The same issue was placed before the court, whether the trial court improperly imposed a downward sentence on the basis of overcrowding of prisons due to COVID-19. The Second District held that the generalized concerns of the trial court for overcrowding could not serve as valid grounds because it was not consistent with legislative sentencing policy and there was no caselaw to supports its contention. Second, in that case the defendant failed to present substantial evidence of his request for a departure sentence, and it was not clear if a previous release the defendant had was based on overcrowding or the pandemic, the court ultimately held that the evidence was insufficient.

Here, the Court agreed with the sister court, although Mr. Jones had been in a pretrial house arrest while awaiting his trial, this was not enough to support cause for legislative sentencing. Second, as noted by the Court “the Covid virus is so rampant and continues to be so rampant in the county jail and in the prison.” Therefore, because Mr. Jones failed to provide substantial evidence that he had any underlying medical condition which placed him at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 his claim for a departure sentence fails.

SOURCES:

- https://www.3dca.flcourts.org/content/download/828097/opinion/201220_DC13_02092022_100138_i.pdf

- State v. Saunders, 322 So. 3d 763, 767 (Fla. 2d DCA 2021.

by Crystal Barranco Garcia | Feb 14, 2022 | Moot Court Mondays

On February 3, 2022 the Supreme Court of Florida approved proposed amendments to the Florida Rules of Juvenile Procedure; and it seems more change is coming from the legislature. The new trend is showing a broadening of rights and protections for juveniles. Among the rules that were amended and/or added are, 8.217, 8.305, and 8.345. Although there were many important changes approved these are some of the most important ones. First, rule 8.217 now adds the words “attorney for the child” when the caregiver has objected to “a change in the child’s physical custody placement.”2 This differs from the previous rule which only required the child have attorney ad litem.3 Another amended rule is 8.305 which now prioritizes “out-of-home placements, including fictive kin, or nonrelatives.” Lastly, rule 8.345 which focuses on Post-Disposition Relief has been amended so that it now provides that “a hearing must be held if any party or the current caregiver denies the need for a change [to custody placement] and creates a rebuttable presumption that it is in the child’s best interest to remain permanently in the current physical placement if certain conditions are present.”

On February 3, 2022 the Supreme Court of Florida approved proposed amendments to the Florida Rules of Juvenile Procedure; and it seems more change is coming from the legislature. The new trend is showing a broadening of rights and protections for juveniles. Among the rules that were amended and/or added are, 8.217, 8.305, and 8.345. Although there were many important changes approved these are some of the most important ones. First, rule 8.217 now adds the words “attorney for the child” when the caregiver has objected to “a change in the child’s physical custody placement.”2 This differs from the previous rule which only required the child have attorney ad litem.3 Another amended rule is 8.305 which now prioritizes “out-of-home placements, including fictive kin, or nonrelatives.” Lastly, rule 8.345 which focuses on Post-Disposition Relief has been amended so that it now provides that “a hearing must be held if any party or the current caregiver denies the need for a change [to custody placement] and creates a rebuttable presumption that it is in the child’s best interest to remain permanently in the current physical placement if certain conditions are present.”

It seems that these newly proposed amendments are just some in the new era of juvenile procedural change. The Florida Senate approved this same week a juvenile expungement bill. This bill would “broaden a juvenile’s ability to expunge their arrest record in Florida.”4 This would favor the juvenile clients that want to continue a life free of the bitter reminder of their conviction. Now more than ever Florida attorneys need to keep a close eye to the changes coming to juvenile law. Time to shepardize the law.

Sources:

1 https://www.jmcdowelllaw.com/juvenile-law-common-misconceptions/

2 https://www.floridasupremecourt.org/content/download/826484/opinion/sC21-1681.pdf

3 An attorney ad litem is a court-appointed lawyer who represents a child during the course of a legal action, such as a divorce, termination, or child-abuse case. The attorney owes to the child the duties of loyalty, confidentiality, and competent representation. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/ad_litem

4 https://floridapolitics.com/archives/495260-juvenile-expunction-bill-advances-through-final-senate-committee-stop/

3M corporation, long a staple of American industry, has recently been rocked by a string of lawsuits related to defective earplugs it sold to the U.S. military in what has been termed the largest multi-district litigation in U.S. history.1 As of the writing of this article, plaintiffs (all former U.S. military veterans have been awarded a staggering combined amount of $160 million in six bellwether trials.2 The entire controversy stems from 3M’s 2008 acquisition of Aearo Technologies, the company which manufactured the earplugs.3 The reason Aearo’s design of earplugs appealed to the U.S. military resulted from its innovative design: the dual-ended design allowed one end to block out as much sound as possible while the other end protected a user’s ears from extremely loud noises such as gunfire or explosions.4 This design was advantageous because it allowed troops to communicate with fellow soldiers nearby during loud situations.5

3M corporation, long a staple of American industry, has recently been rocked by a string of lawsuits related to defective earplugs it sold to the U.S. military in what has been termed the largest multi-district litigation in U.S. history.1 As of the writing of this article, plaintiffs (all former U.S. military veterans have been awarded a staggering combined amount of $160 million in six bellwether trials.2 The entire controversy stems from 3M’s 2008 acquisition of Aearo Technologies, the company which manufactured the earplugs.3 The reason Aearo’s design of earplugs appealed to the U.S. military resulted from its innovative design: the dual-ended design allowed one end to block out as much sound as possible while the other end protected a user’s ears from extremely loud noises such as gunfire or explosions.4 This design was advantageous because it allowed troops to communicate with fellow soldiers nearby during loud situations.5

The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) of 2000, provides that no substantial burden can be imposes on the religious exercise of a person, including state prisoners, unless the imposed burden is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest. However, RLUIPA only protects a prisoner’s requested accommodation when it is sincerely based on a religious belief and not some other motivation.

The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) of 2000, provides that no substantial burden can be imposes on the religious exercise of a person, including state prisoners, unless the imposed burden is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest. However, RLUIPA only protects a prisoner’s requested accommodation when it is sincerely based on a religious belief and not some other motivation.

Android, built on Java software code, provides power to a majority of the mobile devices in the world. Android was developed and run by technology super house Google. Google states that they used elements of this Java code for operations. This methodology, originally spun by the technology giant Oracle, led to a public feud in 2011. Oracle claimed Google had copyrighted exact lines of a Java code they had created to complete their technology development. Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021).

Android, built on Java software code, provides power to a majority of the mobile devices in the world. Android was developed and run by technology super house Google. Google states that they used elements of this Java code for operations. This methodology, originally spun by the technology giant Oracle, led to a public feud in 2011. Oracle claimed Google had copyrighted exact lines of a Java code they had created to complete their technology development. Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021).

The Establishment Clause is a clause that comes from the First Amendment of the United States. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”.

The Establishment Clause is a clause that comes from the First Amendment of the United States. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”.

Covid has brought about many changes in the United States legal system, specifically in the context of incarceration. In this recent opinion the Defendant, Mr. Jones (“Mr. Jones”), was convicted pursuant to Criminal Punishment Code Scoresheet, Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 9.992. The lowest sentencing that was provided to Mr. Jones was twenty-one months in state prison. Due to the onset of COVID the sentencing was delayed, and Mr. Jones sought an alternative sentencing of two years in community control followed by a three-year probation. Ms. Jones was ultimately asking the Court to allow for a longer sentencing outside of prison to prevent contracting COVID-19. At the time of his sentencing the current statistics provided that over 31,000 Floridians had tested positive for COVID-19 including over 1,000 deaths. Mr. Jones was also fifty years old at the time of his sentencing and the sole medical issue he pointed to be the testimony of father that claimed he had high blood pressure. However, the basis of the argument was not on the medical condition itself, but on the global pandemic.

Covid has brought about many changes in the United States legal system, specifically in the context of incarceration. In this recent opinion the Defendant, Mr. Jones (“Mr. Jones”), was convicted pursuant to Criminal Punishment Code Scoresheet, Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 9.992. The lowest sentencing that was provided to Mr. Jones was twenty-one months in state prison. Due to the onset of COVID the sentencing was delayed, and Mr. Jones sought an alternative sentencing of two years in community control followed by a three-year probation. Ms. Jones was ultimately asking the Court to allow for a longer sentencing outside of prison to prevent contracting COVID-19. At the time of his sentencing the current statistics provided that over 31,000 Floridians had tested positive for COVID-19 including over 1,000 deaths. Mr. Jones was also fifty years old at the time of his sentencing and the sole medical issue he pointed to be the testimony of father that claimed he had high blood pressure. However, the basis of the argument was not on the medical condition itself, but on the global pandemic.

On February 3, 2022 the Supreme Court of Florida approved proposed amendments to the Florida Rules of Juvenile Procedure; and it seems more change is coming from the legislature. The new trend is showing a broadening of rights and protections for juveniles. Among the rules that were amended and/or added are, 8.217, 8.305, and 8.345. Although there were many important changes approved these are some of the most important ones. First, rule 8.217 now adds the words “attorney for the child” when the caregiver has objected to “a change in the child’s physical custody placement.”2 This differs from the previous rule which only required the child have attorney ad litem.3 Another amended rule is 8.305 which now prioritizes “out-of-home placements, including fictive kin, or nonrelatives.” Lastly, rule 8.345 which focuses on Post-Disposition Relief has been amended so that it now provides that “a hearing must be held if any party or the current caregiver denies the need for a change [to custody placement] and creates a rebuttable presumption that it is in the child’s best interest to remain permanently in the current physical placement if certain conditions are present.”

On February 3, 2022 the Supreme Court of Florida approved proposed amendments to the Florida Rules of Juvenile Procedure; and it seems more change is coming from the legislature. The new trend is showing a broadening of rights and protections for juveniles. Among the rules that were amended and/or added are, 8.217, 8.305, and 8.345. Although there were many important changes approved these are some of the most important ones. First, rule 8.217 now adds the words “attorney for the child” when the caregiver has objected to “a change in the child’s physical custody placement.”2 This differs from the previous rule which only required the child have attorney ad litem.3 Another amended rule is 8.305 which now prioritizes “out-of-home placements, including fictive kin, or nonrelatives.” Lastly, rule 8.345 which focuses on Post-Disposition Relief has been amended so that it now provides that “a hearing must be held if any party or the current caregiver denies the need for a change [to custody placement] and creates a rebuttable presumption that it is in the child’s best interest to remain permanently in the current physical placement if certain conditions are present.”